By Ahmed Ebeed

In Part 1 we tackled the origin of Arabic Calligraphy and its development from Nomadic to an art. The Tumar script which was used by the caliphs in signatures and in writing to sultans was expounded. And, the kufi script which is characterized by its flexibility and accuracy was also elaborated. Here, in the final part of this series, we will tackle other different types or styles of Arabic Calligraphy such as Naskh, Farsi, Riq`a, and Diwani scripts.

In Part 1 we tackled the origin of Arabic Calligraphy and its development from Nomadic to an art. The Tumar script which was used by the caliphs in signatures and in writing to sultans was expounded. And, the kufi script which is characterized by its flexibility and accuracy was also elaborated. Here, in the final part of this series, we will tackle other different types or styles of Arabic Calligraphy such as Naskh, Farsi, Riq`a, and Diwani scripts.

THE NASKH SCRIPT: THE SERVANT OF THE QUR’AN

Some arguably ascribe the Naskh script to `Abdullah Al-Hassan ibn Muqla, the brother of the calligrapher `Ali ibn Muqla, while others perceive that the Naskh is much older than Ibn Muqla.

Ibn Muqla actually developed the handwriting to its current form, distinguishing it from other handwritings. It was named Naskh (meaning “copy”) because writers used it in the copying of the Qur’an, the Hadith, and other books. It was also used in writing on metal, wood, marble, and plaster. Ibn Muqla named this script Al-Badei` (radiant or exquisite) due to its aesthetic nature. Naskh is close to Thuluth in its beauty, glamour, and accuracy. It is decorated, but to a lesser extent than Thuluth. The tashkil (diacritical signs) add to its beauty and elegance.

Naskh script is considered as an element of decoration and gained much attention in Iraq in the Abbasid era. It was developed in the Atabiki age, which started around AH 545, and was known as the Atabiki Naskh. It was used in the writing of the Qur’an in the Islamic middle ages and it replaced the Kufi script for copying the Qur’an and decorating the walls of the mosques. Both Naskh and Thuluth became the most prevalent scripts. Naskh can be differentiated from Thuluth by the small size of its letters. The size and sequence mean the writer can use the pen more swiftly than when writing the Thuluth, but still retain harmony and beauty.

THE PERSIAN OR FARSI SCRIPT

The Persians used to use the Fahlawi script, which originated in the city of Fehla, which lies between Hamdan, Asfahan, and Azerbaijan.

When Persia was conquered, Persians were introduced to Arabic letters and Arabic became their official handwriting. The Arabic letters replaced the Fahlawi script and it then became known as Ta`liq (cursive) due to its cursive style and horizontal forms.

At the beginning of the third century after the Hijrah, after consolidating their position in both Persia and Iraq, the Abbasid Dynasty showed deep interest in Arabic calligraphy. They tended to write in Naskh and they decorated the letters with excessive decoration, to an extent that gave their script a particular character. The Persian script was used in the writing of literature and poetry books; whereas books of Hadith were written in Naskh.

The Persians excelled in the cursive scripts. They added ornaments and decorations that made the script unique with its beautiful inclined letters. Letters changed in length and thickness according to the taste of the artist and the thickness of the pen. Letters were unique for their accuracy and extension and they bore no formations. Persian script was used to write the titles of books and letters, and is widely used in Iran, India, and Afghanistan.

Types of Persian Script

1. The Ordinary Persian: Known in our time in foreign countries as Al-Ta`liq.

2. The Shikista script: This is small and very difficult to read or to write. This kind of handwriting does not follow the ordinary rules of handwriting, but has its own rules. Shiksta means “broken” in Persian and in Turkish it means “the cursive formula.” This kind of handwriting is rather an enigma, a complicated riddle. It is even hard for Arabs to decipher writings in that script; whereas in Persia, only those who have mastered it can understand it.

3. Shikista Emir: This is a combination of the two types, the Ordinary and the Shikista. It is less enigmatic than the other kind. Manuscripts, texts of legislative documents, and books of literature and poetry were written in Shikista Emir and ornamented with golden decorations.

RIQ’A STYLE OF HANDWRITING: A QUICK RYTHM

The Riq`a style of handwriting is one of the “modern” types of handwriting. It was said to have been invented by Mr. Mumtaz Bek Mustafa Effendi, the counselor, who set its rules in AH 1280, in the reign of Sultan `Abd Al-Majdi Khan, although some believe that the Riq`a goes back to the time of Sultan Muhammad Al-Fateh.

The Riq`a style of handwriting is one of the “modern” types of handwriting. It was said to have been invented by Mr. Mumtaz Bek Mustafa Effendi, the counselor, who set its rules in AH 1280, in the reign of Sultan `Abd Al-Majdi Khan, although some believe that the Riq`a goes back to the time of Sultan Muhammad Al-Fateh.

This style of handwriting is known for its clipped letters. It was probably derived from the Thuluth and Naskh styles. Riq`a is a beautiful script known for its straight lines. It does not entail any formation. It is clear and readable and is the easiest of all kinds for daily handwriting. In the beginning, it was the most common for daily use, especially for women. It is used in the titles of books and magazines and in commercial advertisements, thanks to its simplicity and clearness. The simplicity of the Riq`a is attributed to the simple geometric formation of its letters, which are reliant on easily formed straight lines and circles.

THE DIWANI SCRIPT: THE SCRIPT OF ELOQUENCE

This style of handwriting goes back to the Ottoman period. It was labeled the Diwani script because it was used in the Ottoman dawaween (bureaus) and was one of the secrets of the palaces of the sultan. The rules of this script were not known to everyone, but confined to its masters and a few bright students. It was used in the writing of all royal decrees, endowments, and resolutions.

The Diwani style spread enormously in modern times due to the efforts of the Royal Arabic Calligraphy School in Egypt. It was simplified and developed by the Egyptian calligrapher Mustafa Ghazlan; hence it was called the Ghazlani handwriting.

The Diwani script is divided into two types.

1. The Riq`a Diwani style, which is void of any decorations and whose lines are straight, except for the lower parts of the letters.

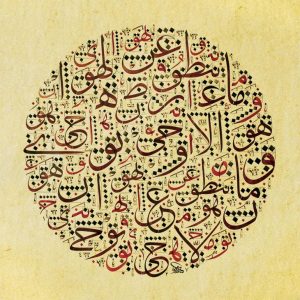

2. The Jali or clear style. This kind of handwriting is distinguished by the intertwining of its letters and its straight lines from top to bottom. It is punctuated and decorated to appear as one piece. The Diwani handwriting is known for the intertwining of its letters, which makes it very difficult to read or write—and difficult to forge!

Diwani is marked by beauty and harmony. Accurate small samples are usually more beautiful than big ones. This kind of handwriting is still used in the correspondence of kings, princes, presidents, and in ceremonies and greeting cards. It has a high artistic value.

REFERENCES

– `Afif Bahnasi. Al-Khat Al-`Arabi: Usuluh, Nahdatuh, Intisharuh (Arabic Calligraphy: Principles, Development, Spread). 1984. Damascus: Dar Al-Fikr.

– Basim Zanoun. Al-Khat Al-`Arabi: Rihlat Al-Tahsien wa Al-Tajwid (Arab Calligraphy: Journey of Improvement & Embellishment). 1998. Egypt: Dar Al-Kitab.

– Yehya Wahin Al-Jaboury. Al-Khat wa Al-Kitabh fi Al-Hadarah Al-`Arabiah (Calligraphy and Handwriting in the Arab Civilization). 1994. Morroco: Dar Al-Gharb Al-Islami.

– `Abdul `Aziz Al-Dali. Al-Khataath: Al-Kitab Al-`Arabih (Calligraphy: Arabic Handwriting). 1992. Egypt: Al-Kahnjy.

———————————-

Courtesy www.nur-ar-ramadan.tripod.com with slight editorial modifications.

Ahmed Ebeed was the head of Information Unit in IslamOnline.net (IOL). He has a deep interest in Arabic calligraphy.

Soucre Link